Excerpt:

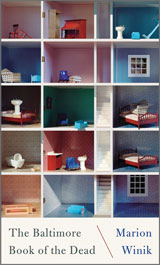

The Baltimore Book of the Dead

Description

Press

|

|

Here are four of the 61 portraits — mini-essays or prose-poems — that make up the book.

The Alpha

died 2008

Anyone who was at Camp Nawita in the late 1930s can tell you, she was queen of the baseball diamond. The tennis court, the hockey field, the horseshoe pitch, and the lake. Too bad she beat Title IX by forty years. It wasn't exactly the heyday of female business majors, either, nor women in the workplace, and for a really bad idea, try sending a young woman on a business trip by herself, wedding ring or no. Enough already. She got pregnant, moved to the Shore, took up golf and gin. She won her first club championship in 1966, just as I began my poetry career. I raced into the dining room where she was drinking her martini, ode in hand. She had a bad lie in the weeds of sixteen / Ere she lofted and landed her ball on the green. Now I haven't set eyes on that place in ten years, and when they say everything is different, I believe them.

Everyone's mother is mythological: her body the origin of existence and consciousness, her house the pimped-out crib of Zeus, her mistakes the cause of everything. Holy her rose bushes, holy her blackjack system, her London broil holy. My mother, the godhead of 7 Dwight Drive, rose daily from her bed to quaff her Tropicana orange juice and to slay the New York Times crossword puzzle. She survived a difficult childhood, my father's high jinks, two heart attacks, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, surgery for diverticulosis, and the many poor decisions and inappropriate outfits of her daughters. She certainly did not believe a clot in her lung could bring her down, that smoking for sixty-five years would actually cause lung cancer, or that lung cancer was definitely fatal. The last thing she did before she took to her bed was win a golf tournament. Clearly the subprime crisis, the market crash, Hurricane Sandy, and even Donald Trump were biding their time until she was out of the way.

And then she was. Imagine Persephone coming up from hell and Demeter not there. Strange cars in the driveway, the rose bushes skeletons. You stand there at first, uncomprehending, your poem in your hand. Then you go somewhere, call it home. Call it spring.

Who Dat

died 2013

The bar for "crazy" is high in New Orleans. Same with "alcoholic" and "drug addict." I once heard someone there explain that he knew he didn't have a drinking problem because he stayed in on Fridays. This aspect of the city's culture made me feel right at home when I arrived in the early eighties. My New Orleans hosts were a couple of old friends who had moved down from New York State. Now they were birds of a feather in a flock of odd ducks: underground musicians, visual artists, psychics, conspiracy theorists, voodoo queens. Their main man and direct line into the indigenous New Orleans music scene was a cadaverous guitar player who, still in his twenties, was already a legend. Though his style was more experimental punk than funk or blues, his band was everywhere, opening for the Meters or Professor Longhair, backing up Earl King or Little Queenie. He was widely considered the city's best songwriter, though few could name a single song he'd written.

Little he said made logical sense, and he was impossible to pin down about anything. His eyes looked sad all the time. He had a young son and a wife, later another wife, and he was devoted to all of them. He was kind. Acutely aware of the invisible things around us, he had personal experience with alien abduction. He also had amazing drug connections. So amazing he eventually had to leave New Orleans to get away from them and wound up living in voluntary exile for the rest of his life.

One time, we stopped in Atlanta to visit him and his wife. They had a rambling, two-story house with a huge kitchen. Diane took us to the farmers' market, where I bought three bunches of Swiss chard for a pasta dish from Sundays at Moosewood. The details of that recipe are the thing I remember best in this whole story. Ziti con bietole. Try it.

Though we had been out of touch for decades, he found me on Facebook and called when he learned he was dying. He was sixty-two, diagnosed with Stage IV cancer, and since I had written about my role in Tony's assisted suicide, he wondered if I had any ideas for him. Other than that, he just wanted to say hey.

The Thin White Duke

died 2016

There are two kinds of rock star: the kind you want to sleep with, and the kind you want to be — though in most cases either would be fine. A poet friend told me that the high point of her life was when she appeared as Ziggy Stardust at a twenty-fifth-anniversary celebration of the album at Yale. (A second-generation fan, she was not even born when we were listening to Hunky Dory on endless loop in 1971.) She cut off her hair, dyed it red, wore a jumpsuit and silver platform boots. She sang every song on the album. Though this was the entire history of her career as a vocalist, she was so carried off by euphoria that she married the drummer.

In my early adolescence, I had a kind of mild gender dysphoria, though I have only learned that term relatively recently. Nagged by the feeling that things would be working out better for me if I'd been born a boy, one summer at camp I told people my name was Mike. It wasn't that I was attracted to girls. In fact, the teenage me was more interested in gay men than gay women, making continual heroic efforts to be admitted to El Moroccan Room, a drag club in Asbury Park. Gender, sexuality, art, music, rebellion: all of this made more sense because of him. He gave us a bigger space to decide who to be.

Of his many performance personae — Ziggy Stardust, Major Tom, Aladdin Sane, Screaming Lord Byron, The Goblin King — The Thin White Duke was definitely the worst idea. A stylish blond neo-romantic hero, the Aryan Duke caused a hullabaloo by saying things like Hitler was the first rock star. Bowie later explained that he was doing so much cocaine at this time that he had no memory of even recording the album Station to Station (one of my favorites, his haunting, shaky cover of "Wild Is the Wind," comes from this period). He ended it by moving away from Los Angeles. Luckily, what usually happens to rock stars when drugs get the better of them happened only to The Thin White Duke, not his creator. David Bowie lived another forty years, even completing an afterword to his body of work in "Lazarus." He was leaving his cell phone down here, he said, to be free.

The Belligerent Stream

buried 1962

Everyone who drives into Baltimore is shocked to discover that the interstate — a part of I-83 known as the JFX — stops dead and disappears in the middle of town. Whether you are coming from the north or the south, your route into the city will dump you off near the Inner Harbor and leave you to wend your way through downtown traffic. Before the JFX vanishes, it wanders through town like a drunk, swerving drastically left, then right, for no apparent reason.

But there is a reason. This road is built right on top of the Jones Falls, which once burbled through town to the bay, a "belligerent stream" according to early twentieth-century historian Letitia Stockett, who taught at the high school my daughter now attends. Perhaps because it was always prone to flooding and filled with trash, few mourned in the 1960s when the tough little waterway was paved over, sacrificed to suburbanites' need for speed. The alternative was tearing down buildings and slicing through neighborhoods. On the other hand, if they had finished the road as planned, the Inner Harbor would now be covered with concrete ramps. A terrible thought indeed. Though it didn't look like much back then, the decaying port has since become the city's sparkly little Disneyland; all of Baltimore most tourists ever see.

Meanwhile, the belligerent stream has never submitted entirely, as I learned recently while reading a novel set in Baltimore with a secret waterfall. I immediately emailed the author: Where is this? In the abandoned industrial neighborhood beneath the elevated part of the highway, he wrote back, look for an overgrown trail. Once we found it, my daughter had to help me down the steep makeshift steps to the rickety deck. And there it was: the surprisingly emerald waters of the Jones Falls, bursting out of the culvert, rushing to a rounded cliff, tumbling over and pounding noisily into a pool. Graffiti adds a caption to the postcard: PERSISTENCE IS KEY.

Excerpted from The Baltimore Book of the Dead, Marion Winik (Counterpoint, 2018). Reprinted with permission of the author.

|